Meet the Experts keep children safe

Keeping the children safe

New EU rules about which chemicals can be used in toy jewellery or kids’ pieces cannot be ignored. We asked Assay Office Birmingham’s Michelle Cartwright to talk us through the issues.

Product safety is becoming increasingly regulated within the EU and this having a significant impact on the jewellery and watch industry. The burden is felt particularly heavily in the case of children’s jewellery which tends to sell for a lower price, partly due to its smaller size and also due to market forces.

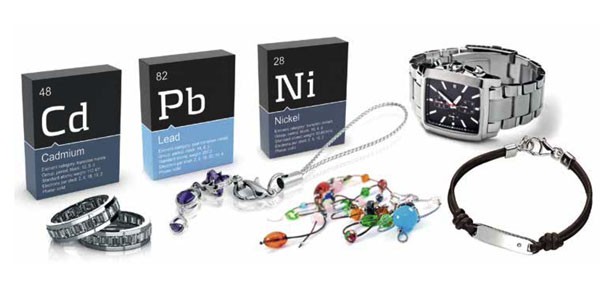

Precious metal jewellery is unlikely to cause too many problems, so long as it complies with the nickel regulations which have been enforceable for 13 years now. However, new regulations included in the extensive REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation & restriction of Chemicals) regulation have required importers and manufacturers of jewellery of all types to demonstrate compliance with much more stringent requirements.

Michelle Cartwright is production manager in AnchorCert Analytical and she says that whilst there is no specific legislation relating to children’s jewellery, “it is clearly caught by REACH regulations relating to nickel, cadmium and, from October 2013, lead.” She adds: “Articles including fabrics and textiles also have to meet compliance levels for azo dyes and formaldehyde and there is a significant amount of testing required.”

There can be no argument that the nickel regulations that apply to all items “intended to come into prolonged and direct contact with the skin” apply. As with so many other hazards, this is particularly important for children’s products, as exposure to nickel, most commonly through a fresh body piercing, can cause nickel sensitisation for life. Once sensitised, any exposure to nickel can cause a severe allergic reaction.

Historically, nickel was commonly used in fashion jewellery due its bright whiteness, excellent bleaching qualities and the increasing durability it brings to an alloy. Cartwright explains: “Very few of the items we test now fail nickel and the biggest culprits are watch crowns. The level of nickel release allowed in post assemblies, which are the most potentially dangerous part of the item in nickel terms, is extremely low and it seems most suppliers have now found a satisfactory alternative.”

Restrictions relating to nickel were followed by the control of cadmium in December 2011. While this legislation is chiefly intended to protect those in the manufacturing part of the supply chain where fumes from molten cadmium can cause severe health hazards, it has imposed a significant cost on the fashion jewellery trade as the legislation clearly requires each material component to be tested separately. Unless a carefully audited, traceable process is in place throughout the supply chain, which is rarely the case, this means that sufficient samples of each material have to be carefully removed from the finished product prior to testing.

This requires painstaking and skilled scraping to separate out the components and is inevitably costly. “The Assay Office invested heavily in hi-tech equipment to cope with the high volumes of samples we are receiving,” says Cartwright. “We have the latest micro digestion system and two additional ICP’s to carry out the analysis but there is no way of deskilling or automating the scraping process, which is incredibly important to the accuracy of the final result. The permitted content for cadmium is only < 100ppm for metals and plastics and < 1,000 ppm for paint, so attention to detail is crucial”

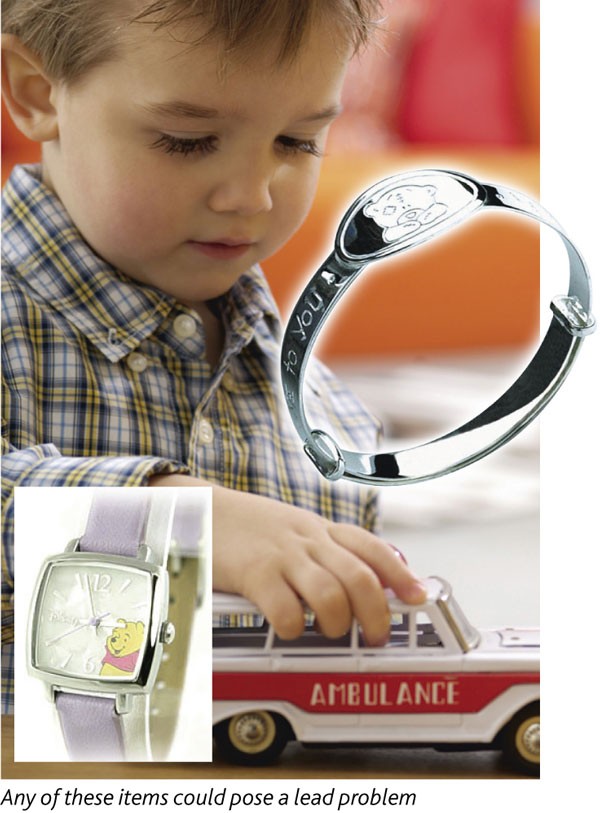

For many years the hazardous substance most readily recognised as a danger to children has been lead, but there has not been any specific legislation relating to lead in children’s jewellery products although it has been restricted in toys. However, lead will be regulated by REACH from 9th October 2013. The regulation determines that “Lead...and its compounds shall not be used in jewellery articles if the lead concentration is equal to or greater than 0.05 per cent (500ppm) by weight of any part of the jewellery article.”

The products covered clearly include both precious and fashion jewellery, intended for use by adults as well as children: “Jewellery and imitation jewellery articles and hair accessories, including bracelets, necklaces and rings, piercing jewellery, wrist-watches and wrist wear, brooches and cufflinks”.

Again, compliance with this legislation is most important in children’s products. Regular exposure to lead causes the toxin to gradually accumulate within the body which can cause severe developmental and behavioural problems. This can easily happen if a child is sucking on, or “mouthing” a product which is releasing lead.

Likewise, accidentally swallowing a complete item containing a high lead content can have very severe consequences as the lead leaches into the body and may even prove fatal. So how can one perform a reasonable risk assessment? Cartwright thinks it is “very unlikely that precious metal jewellery will contain more than the permitted levels of lead”, but adds that “coated base metal items, where the coating may easily wear off are always a risk and the non-metallic parts, particularly glass stones are definitely the highest risk as lead is commonly found in plastics, varnishes, paints, enamels and lacquers.

“At Assay Office Birmingham we interpret the legislation as requiring us to test each of these material components separately, as is clearly the case for cadmium. These two tests can then be carried out simultaneously. The testing is definitely worthwhile as we do find individual paints, plastics and particularly stones that are non compliant.”

Crystals, precious and semi-precious stones are not restricted as the lead in these stones is unlikely to migrate from the stones and cause any harm. However, if the stones are treated with lead or its compounds they do still need to comply. The General Product Safety Directive defines a ‘safe’ product as one that “under normal or reasonably foreseeable conditions of use including duration does not present any risk or only the minimum risks compatible with the product’s use”.

It requires that, in the absence of any specific legislation, items should still be classified as ‘safe’ in this respect. Historically, in the absence of any specific regulation for lead, retailers, aware of its potential harmful properties, have been asking the supply chain to test children’s products to EN71-3 – the standard relating to the migration of toxic elements in the Toy Safety Regulation.

In July this year, this test was extended to include 19 elements, instead of the original eight. However, it must be stressed that compliance with this test is not a specific legal requirement for children’s jewellery. Most children’s jewellery products do not fit the Toy Regulations definition of “products designed or intended, whether or not exclusively, for use in play by children under 14 years of age”. It will be interesting to see how legal departments advise retailers in respect of straightforward metal jewellery items once lead is officially included in REACH from October 2013.

Your item has been added to the basket

You need to create an account, or login before you can add this item to your basket.

Michelle Cartwright has worked in The Laboratory for 21 years, and holds the trusted position of melt and assay co-ordinator, responsible for overseeing the movement of scrap gold submitted for melt and assaying. Cartwright’s position as administration and production manager sees her taking responsibility for organising and managing the day-to-day workflow through The Laboratory ensuring that the highest level of service is provided to customers of this growing division. Michelle is also a qualified metallurgist – an engineer trained in the extraction and refining and alloying and fabrication of metals.

Michelle Cartwright has worked in The Laboratory for 21 years, and holds the trusted position of melt and assay co-ordinator, responsible for overseeing the movement of scrap gold submitted for melt and assaying. Cartwright’s position as administration and production manager sees her taking responsibility for organising and managing the day-to-day workflow through The Laboratory ensuring that the highest level of service is provided to customers of this growing division. Michelle is also a qualified metallurgist – an engineer trained in the extraction and refining and alloying and fabrication of metals.